Dawn 黎明

Solo Exhibition, Art-2 Gallery, 2002

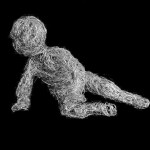

I encounter thirty-six tiny babies in the incubation site that is Victor Tan’s studio. Their movements are curious and playful, soft and natural. That they are made of wire is perhaps even more curious, and I cannot decide whether to examine the sculptor’s motive behind these dedicated pieces, or to just pick them up and examine them for myself.

I encounter thirty-six tiny babies in the incubation site that is Victor Tan’s studio. Their movements are curious and playful, soft and natural. That they are made of wire is perhaps even more curious, and I cannot decide whether to examine the sculptor’s motive behind these dedicated pieces, or to just pick them up and examine them for myself.

“There is wisdom in these movements, there is no need to teach babies how to move, but their movements mature day by day. I have been working on my niece Jeauree since she was six to ten months old, and I have continued capturing her movements and growth. She’s now one year and four months, now she walks,” Tan comments with enthusiasm.

The majority of Victor Tan’s sculpture has been centered on the human figure, but he has in the past generally used the adult form, generally without gender, to examine and to release a variety of emotions and wonderings. The earliest pieces were classical in approach, portraying various ‘grand’ emotions in an evocation of human postures that recall Greek tragic heroes and antiheroes. These were Tan’s primary renderings, searching for a language and a voice to work through his own anxieties, heartbreaks and traumas. And indeed one would recognize the human pathos and also trauma in those first figures, woven with fingers trying to communicate in a language that was beyond what Tan would communicate verbally.

Now five years into his practice as a professional sculptor Tan has achieved several milestones for himself. The small sketches had been enlarged successfully into larger-than-life works, the first of this, not surprisingly, being a series on human communication and connection titled “Okay”, (1998). Here Tan had experimented with various poses to make a dramatic pageant where five human figures represent the fingers of a hand making the ‘OK’ sign. This work has its strength not in the story that Tan has enacted, but in the construction of a strong visual piece with playful connotations. The positive energy of the work is reinforced by deft sculpturing. I believe its success is due to the emotional factors of the work being in correlation with Tan’s own personal breakthrough.

The next major piece “Between”, (1999), was a series of entrances; the human figure, again larger-than-life-size, crossing through a frame into a new space. The crossing over concept could be seen again as a personal milestone, Tan gaining new confidence as an artist, and the new beginnings that were happening in both his art and his life were uplifting breakthroughs. The effect of Tan working in series meant that he could follow a suite of movements to make different statements with each work. This Tan developed with “Dawn to Dusk”, (2000), where visual element, form and content united to make all five pieces into one inseparable composition. Apart from the “Born” baby sculptures from 1999, this was one work where Tan had begun to use the infant form.

The first babies were made in London where Tan was working out his prize, the Commonwealth Art Award which allowed him his choice to understudy the sculptor Bryan Ellery. In London, where Tan met many people who were single parents, he was impressed by his encounters with their infants, and the experience of holding a child in his arms was emotional and lasting.

Inspired, he managed to find an extremely life-like toy to work from, resulting in the exhibition “Born”, (2000), where Tan featured a series of almost life-size new-borns in various positions. But the real study began over a year later with Jeau Ree, whom Tan found totally irresistible. To Tan, holding the child was something he described as being the most natural of feelings and experiences. This was a pure experience of a person, an unconditional trusting and loving relationship that was new to the artist.

Another concurrent development in Tan’s life was his becoming more aware and conscious of the subtlety of movements in his surroundings and in the people near him. He would ‘meditate’ on the infant’s movements, trying to be conscious of every flex of her little body. Thus the serialisation of movements in this exhibition “Dawn”, where Tan traces the series of movements, postures and emotions of the child over more than thirty small sculptures.

This is what I have been confronted with when I enter the studio, and the first thoughts that enter my mind are the words “endearing” and “delightful”. If Tan was seeking to portray innocence, he has succeeded with these fragile-looking small sculptures. But he has achieved more than that — their limbs speak of endeavour, learning, balance, reaching out.

In the previous series “Awareness of Being”, (2001) exhibited in “Between Two and Three”, (2001), Tan used the adult human form to trace the gentle rising and dropping movements of a person. Made with a very light and loose weave of wire, the work has a performative dimension, whilst being set up as an artistic installation. This meditative work with its surreal beauty is also necessarily impersonal and has a transient air. It also established Tan as an artist working within a contemporary vehicle and being able to use the space and environment given him to assemble his work fluently.

The babies, however, have character, and there is little intellectualizing about these sculptures. The documentation is relentless and there is perfection as well as awkwardness in their movements, trying, stumbling, getting up, flaying out, lying peacefully; all totally without self-consciousness. I can almost feel the intensity of Tan’s pursuit to document the child as she made her first movements. “Every moment is a beginning,” says Tan of the child, and so too for the sculptures.

“This is just the beginning of the series – my idea of the child and the reflection of myself as an adult. All of us are in process of being formed, changed. Yet there is a sense of the child within, looking out. That is my experience, like being in a pipe, we are moving from darkness to light. It is the moment of waking up. Art allows me to note this precious life I have now. I hear about children carrying arms and fighting in wars – that is so weird because children don’t have territory. Can’t we have a different situation by caring for each other? If only one could go back to that stage of the child; loving the child and loving the inner child. If I could do my work to make people who are fighting now change their minds, to touch them and get them connected, I would like to.”

Seah Tzi-Yan, Curator, August 2002

Publications

2002 Arts Magazine- (PDF – 1.4MB)

2002 Lianhezaobao (PDF – 165kb)

个展,Art-2画廊,2002年

我在”孵化室”遇到了 36 个小婴儿,也就是陈为达的工作室。他们的动作令人好奇又俏皮,柔和又自然。它们是由不锈钢铁线制成的,这也许更令人好奇,我无法决定是否要通过雕塑家作品背后的动机来理解雕塑,或者直接把他们抱起来,亲自检视它们。

“这些动作都是有智慧的,不需要教宝宝怎么动,但他们的动作会一天天成熟。从我的侄女 Jeauree 六到十个月大时,我就一直在研究她,并持续捕捉她的动作和成长。她现在一岁四个月大了,已经可以走路了。”陈为达兴奋地评论道。

陈为达的雕塑大部分以人物为中心,但他过去一般以成人的形态,一般没有性别,来审视和释放各种情感与疑问。最早的作品采用古典手法,以人类姿势描绘各种“宏大”情感,让人想起希腊悲剧英雄和反英雄。这些是陈为达的主要表现,寻找一种语言和一种声音来缓解他自己的焦虑、心碎和创伤。事实上,人们会在最初的人物中认识到人类的悲情和创伤,这些人物用手指编织,试图用一种超出谭口头交流的语言进行交流。

现在,陈为达作为专业雕塑家已经五年了,他为自己实现了几个里程碑。这些小草图已成功地放大为具有传奇色彩的作品,不出意料,其中的第一幅作品是一系列关于人类交流和联系的作品,名为“Okay”(1998)。在这里,陈为达尝试了各种姿势来制作一场戏剧性的盛会,其中五个人物代表一只手的手指,做出“OK”的手势。这部作品的优势不在于陈为达所演绎的故事,而在于构建了一个具有有趣内涵的强烈视觉作品。巧妙的雕刻强化了作品的正能量。我认为它的成功是由于作品的情感因素与陈为达自己的个人突破相关。

下一个主要作品 “Between”(1999)是一系列的入口;人物形象再次大于真人大小,穿过框架进入一个新的空间。这个跨界概念可以再次被视为个人的里程碑,陈为达获得了作为艺术家的新信心,而他的艺术和生活中发生的新开始都是令人振奋的突破。陈为达的系列作品的效果意味着他可以遵循一套动作对每件作品做出不同的陈述。这种棕褐色是随着《黎明到黄昏》(2000)而发展起来的,其中视觉元素、形式和内容结合在一起,使所有五件作品成为一个不可分割的作品。除了1999年的《诞生》婴儿雕塑之外,这是陈为达先生开始使用婴儿形态的一件作品。

第一个婴儿是在伦敦制造的,陈为达当时正在那里准备他的奖项——英联邦艺术奖,这使他能够选择代替雕塑家布莱恩·埃勒里 (Bryan Ellery) 学习。在伦敦,陈为达遇到了许多单亲父母,与他们的婴儿的接触给他留下了深刻的印象,而将孩子抱在怀里的经历是情感丰富且持久的。

他因此受到启发,设法找到了一个极其逼真的玩具来摸索,从而产生了展览“诞生”(2000),其中陈为达展示了一系列几乎与真人大小的处于不同位置的新生儿。但真正的研究是在一年多后开始的,对象是Jeauree,陈为达发现她完全无法抗拒。对于陈为达来说,抱着孩子是最自然的感受和经历。这是一个人的纯粹体验,一种无条件的信任和爱的关系,对艺术家来说是全新的。

陈为达生活中另一个同时发生的发展是,他变得更加了解和意识到周围环境和周围人的微妙动作。他会“冥想”婴儿的动作,试图意识到她小小的身体的每一次弯曲。因此,在这次展览“黎明”中,陈为达在三十多件小雕塑上描绘了孩子的一系列动作、姿势和情绪。

这就是我进入工作室时所面临的,第一个进入我脑海的就是“可爱”和“令人愉快”这两个词。如果陈为达试图描绘纯真,那么他通过这些看似脆弱的小雕塑取得了成功。但他取得的成就远不止这些——他们的四肢代表着努力、学习、平衡和伸出援手。

在之前的《存在意识》系列(2001年)和《二与三之间》(2001年)中,陈为达使用成年人的形体来描绘一个人轻柔的上升和下降的动作。该作品由非常轻且松散的不锈钢铁线编织而成,具有表演维度,同时被设置为艺术装置。这种具有超现实之美的冥想作品也必然是客观的,并且具有短暂的气氛。它还使陈为达成为一名在当代车辆中工作的艺术家,并能够利用所提供的空间和环境流畅地组装他的作品。

然而,婴儿们都有自己的性格,而且这些雕塑几乎没有什么智力化的地方。记录是无情的,他们的动作既有完美,也有尴尬,尝试、绊倒、起身、摔倒、平静地躺着;一切都完全没有自我意识。当她做出第一个动作时,我几乎能感觉到陈为达想要记录下她的强烈愿望。 “每一刻都是一个开始,”陈为达谈到孩子时说道,对于雕塑来说也是如此。

“这只是这个系列的开始——我对孩子的看法以及我作为一个成年人的反思。我们所有人都在形成、改变的过程中。然而,有一种内心深处的孩子在向外张望的感觉。这是我的经历,就像在管道中一样,我们正在从黑暗走向光明。这是醒来的时刻。艺术让我记录下我现在拥有的这段宝贵的生活。我听说孩子们携带武器参加战争——这很奇怪,因为孩子们没有领土。难道我们不能通过互相关心来拥有不同的情况吗?要是能回到孩子那个阶段就好了;爱孩子,爱内在的孩子。如果我能尽我的努力让现在正在战斗的人们改变主意,触摸他们并让他们建立联系,我很愿意。”

Seah Tzi-Yan, Curator, August 2002

Publications

2002 Arts Magazine- (PDF – 1.4MB)

2002 Lianhezaobao (PDF – 165kb)